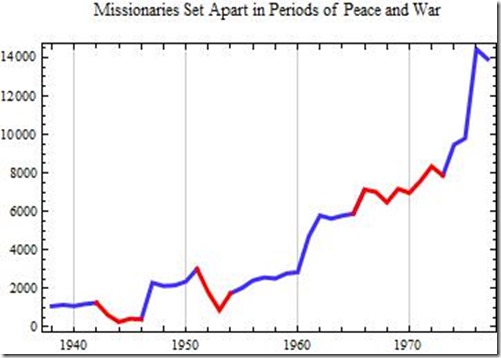

In a previous post (here), I looked at the number of missionaries called during WWII, the Korean War and Vietnam War to build evidence for my hypothesis that the Iraq War was a factor contributing to the decline in missionaries called from 2003 to 2008, The decline in the numbers of missionaries called during WWII and the Korean War as well as statements from church leaders provide some support for the hypothesis but the cause is direct, the draft reduced the number of men available for missions. The evidence provided by the Vietnam War is not as conclusive as that provided by the earlier wars (See graph. Periods of peace are shown in blue, and war, in red). The number of missionaries set apart jumped at the outset of the war in 1965 but grew slowly until the draft ended in 1973. The explanation for the difference between the impact of the draft on missionary numbers between the Korean and Vietnam Wars lies in the implementation of a quota system that allowed missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to take advantage of IV-D deferment for ministers and divinity students.

At the beginning of the Korean War, young men who wanted to serve missions applied for IV-D classification but with varying degrees of success. In some cases, the deferment was granted and in others, not. Church leaders considered using the courts to enforce provisions allowing for the deferment but feared an adverse decision might exclude the deferment for missionaries entirely. As the war progressed, Gordon B. Hinckley was assigned to work with General Lewis Hershey, the head of the Selective Service, to find a solution that accommodated the young men wishing to serve missions and the needs of the military. Hershey was not religious but was of Mennonite ancestry and understood deep religious devotion. (Krehbiel, Nicholas A. “Protector of Conscience, Proponent of Service: General Lewis B. Hershey and Alternative Service during World War II,” Dissertation, Kansas State University, 2009). Few men would have treated the Church as fairly as did Hershey. Hinckley and Hershey established a quota that allowed each ward to set apart one missionary per year. Sheri Dew describes the establishment of the quota system in “Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley.”

Between February 1951 and July 1953, the Church refrained from extending mission calls to young men who were eligible for military service. By that time, the Church’s missionary force had plunged from 4,849 in 1951 to 2,189 in 1953; only 872 missionaries were set apart in 1952. New measures were called for. With General Hershey’s support, and after winning a number of federal appeals, Gordon worked with the Selective Service to achieve what appeared to be a reasonable compromise: a quota that allowed a restricted number of missionaries to serve at any given time. Beginning in July 1953, each ward and branch in the United States could call one young man to serve a mission that year and perhaps two the following year.After the Korean War ended, the military needed fewer men and, as best I can tell, Latter-day Saint men wishing to serve missions were granted IV-D deferments as a matter of course. Peace did not endure. As the Vietnam War escalated, the military through Hershey drafted more men. Looking to avoid military service in an unpopular war, young men sought deferments. The number of men attending college increased (Card, David and Thomas Lemieux. “Going to College to Avoid the Draft: The Unintended Legacy of the Vietnam War,” December 2000), as did the number of men called to serve missions. The number of missionaries set apart in 1965 grew 21% from the previous year to 7,139.

General Hershey, needing more soldiers, wanted restrictions placed on the number of LDS men seeking deferments to preach the gospel. Gordon B. Hinckley and he developed a more generous quota system that would eventually allow two missionaries per ward to be called every year, more generous perhaps because manpower needs were lower. During the height of the Korean War in 1951, 551,806 men were drafted compared to 382,010 in 1966. Again quoting Sheri Dew,

Escalation of the conflict in Vietnam (the number of U.S. troops there increased from 11,200 at the end of 1962 to nearly 200,000 by the end of 1965) had fueled the government’s need for draft-eligible both to serve missions and to be called up in the draft. As before, there were no easy answers. And this time, the steady hand and voice of Stephen L. Richards were not available. Numerous meetings with Selective Service officials, including General Lew B. Hershey, who was still national director, and others with whom Elder Hinckley had worked closely during the Korean crisis, led finally to a First Presidency letter, dated September 22, 1965 in which a new missionary quota was announced: one missionary per ward each six months was allowable, with ward and branch quotas transferrable within stakes and districts.Despite the initial jump in missionaries set apart in 1965, the draft through the quota system lowered the growth rate of the number of missionaries serving. Between 1949 and 1973, the number of missionaries set apart increased at an annual rate of 6.0%. Between 1964 and 1969, the year the draft lottery was instituted, the number of missionaries set apart increased by only 3.4% implying that the initial increase the missionaries was offset by slow growth in the remaining years of the Vietnam War. In conclusion, the Vietnam War, like WWII and the Korean War, hurt missionary growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment